I’ve been translating literary works since 2002, navigating voices across English and Turkish with care and precision. My most recent work is Dan Simmons’ Hyperion, and I’m currently deep in the translation of Infinite Jest—a long-haul journey through language and form.

Please find below a selection of my published translations.

[IN PROGRESS] David Foster Wallace – Infinite Jest – 2026

Translating Infinite Jest into Turkish has been a five-year journey, and with only about 50 pages left, I find myself walking alongside the book’s many voices more fluently than ever. Early on, the challenge was sheer survival: untangling Wallace’s syntactic acrobatics, adapting intricate slang and institutional jargon, and reconstructing sentences that resist finality. But over time, a rhythm emerged—a deep, dialogic attention between English and Turkish, where the aim wasn’t to replicate surface effects but to mirror the book’s psychological density and tonal elasticity. Some passages took days, some just hours, but every page demanded presence, not just technique. Translating Infinite Jest has redefined what it means for me to read, write, and listen.

Dan Simmons – Hyperion – 2025

Translating Hyperion into Turkish has been one of the most demanding and rewarding literary experiences of my career. The novel’s stylistic range—from hardboiled noir to theological speculation—requires constant recalibration. Each pilgrim speaks in a distinct voice, and preserving their tonal shifts while adapting for Turkish syntax and cultural resonance has been both a technical and creative challenge. Given the complexity of Dan Simmons’ prose and ideas, my approach has been slow and deliberate, ensuring fidelity not just to the text but to its deeper emotional and philosophical currents. This project has tested—and expanded—every tool I’ve developed as a translator over the years.

Quentin Tarantino – Once Upon a Time in Hollywood – 2024

Translating this novel into Turkish was like riding shotgun with Tarantino himself—chaotic, exhilarating, and full of detours. The voice is deceptively casual, but the tone shifts constantly: from sleazy insider gossip to poignant interior monologue, from macho bravado to film-geek precision. Navigating these shifts in Turkish required careful tuning, especially when rendering the gritty rhythm of 1960s American slang without lapsing into parody or anachronism. There’s also a peculiar intimacy in translating Tarantino’s digressions—pages about cinema history, TV shows, obscure actors—because you start translating not just a character’s world, but the author’s obsession. It’s the most performative translation I’ve done—part mimicry, part interpretation.

William Gibson – Neuromancer – 2023

Translating Neuromancer has been like decoding a transmission from a future that already slipped past us. Gibson’s language isn’t just stylistic—it creates the world. Every sentence is loaded with rhythm, neologism, half-glimpsed tech, and street-level abrasion. The hardest part has been finding a Turkish equivalent for the novel’s cold, fast, and elliptical tone without flattening its strangeness. At times, it meant inventing terms that feel just slightly wrong in the right way—like the original. Sentence by sentence, I had to let go of perfect clarity and follow the pulse instead. This wasn’t just a linguistic task, but a kind of atmospheric tuning. Translating Neuromancer has changed the way I think about syntax, subtext, and how to build a world without exposition.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula – 2022

Translating Dracula has been an exercise in atmosphere and restraint. The language carries a Victorian formality that must be honored, but not embalmed. Turkish has its own registers of dignity and dread, so my task was to thread those into the epistolary structure without sounding archaic or artificially theatrical. The shifts in voice—from journal entries to letters, telegrams, and newspaper clippings—demanded a constant attunement to tone. Each character speaks differently, even within the limits of 19th-century English decorum, and I worked to make that differentiation feel natural in Turkish. The challenge wasn’t just to deliver horror, but to let the dread seep in slowly, as it does in the original—through detail, rhythm, and silence.

Mary Shelley – Frankenstein – 2021

Translating the 1818 edition of Frankenstein has been like holding a live wire of raw Romantic intensity. Unlike the more polished 1831 version, the original text is fierce, conflicted, and philosophically urgent—its language turbulent rather than refined. Shelley’s sentences often unfold in long, stormy waves, and capturing that momentum in Turkish without losing control has been one of the central challenges. The emotional extremes—self-loathing, ecstatic wonder, moral terror—demanded a tone that’s elevated but still intimate. I focused on preserving the texture of Victor’s manic introspection and the Creature’s poetic rage, keeping their voices distinct but equally haunted. This wasn’t just a story to translate—it was a fevered confession to inhabit.

Alan Moore – The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 1 & 2 – 2018-2020

Translating The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Volumes 1 and 2 was like stepping into a linguistic hall of mirrors—everything is a reference, a pastiche, a layer within a layer. Alan Moore writes with razor precision and encyclopedic density, blending Victorian prose, pulp idioms, and comic-book bravado, often within a single panel. The trick wasn’t just translating dialogue, but reconstructing entire registers of genre and historical voice in Turkish. Every character had to sound like they were torn from a different book, and yet belong to the same mad universe. I had to make constant choices between literal fidelity and tonal mimicry, especially with Mina’s restraint, Quatermain’s brittleness, or Hyde’s monstrous eloquence. And then there’s the typography, the puns, the fake ads, the hidden literary cameos—each demanding its own micro-translation logic. It was a translation, yes—but also an editorial performance, a kind of literary cosplay in Turkish.

George Orwell – Animal Farm – 2019

Translating Animal Farm is deceptively difficult—its clarity is sharp enough to cut. Orwell’s prose looks simple on the surface, but every word carries political weight, symbolic resonance, or tonal control. The challenge was to honor that plainness in Turkish without making it feel flat or diluted. I had to constantly guard against over-explaining, especially in moments of irony or propaganda, where the power lies in understatement. The speeches, slogans, and revisions of the commandments demanded particular care—each phrase had to land with the same double-edge as in English. Most importantly, I aimed to keep the rhythm taut, the tone cool, and the moral sting intact. This translation wasn’t about ornament—it was about precision, compression, and quiet fury.

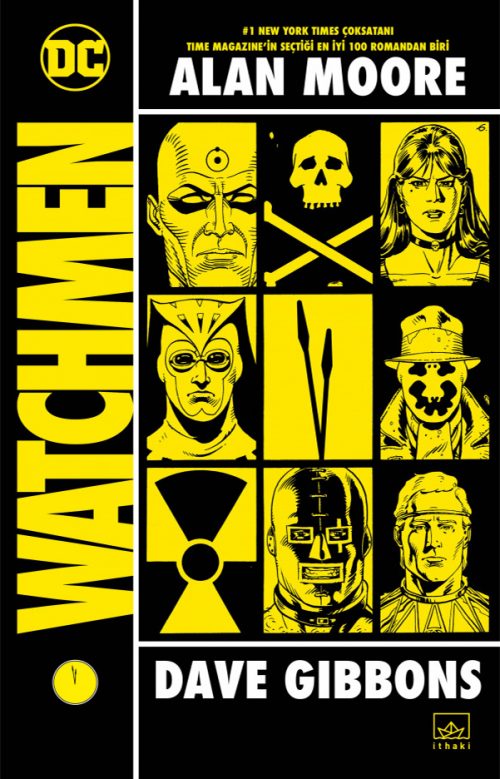

Alan Moore – Watchmen – 2016

Translating Watchmen was like translating time itself—fractured, layered, nonlinear. Alan Moore’s script is dense with symbolism, meta-text, political commentary, and tonal precision, while Dave Gibbons’ visuals carry just as much narrative weight. Every word balloon, caption, and textual insert had to be treated with surgical care. The biggest challenge was syncing the voice to the structure: Rorschach’s clipped, brutal diary entries demanded a raw, broken Turkish; Dr. Manhattan’s philosophical detachment needed an almost sacred cadence; Laurie and Dan’s dialogue had to feel grounded and human in contrast. Then came the Black Freighter comic-within-the-comic, the articles, memos, and faux-historical documents—all requiring distinct registers and controlled variation. Translating Watchmen wasn’t just a linguistic task, it was an architectural one.

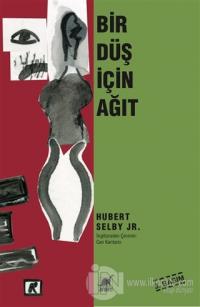

Hubert Selby Jr. – Requiem for a Dream – 2012

Translating Requiem for a Dream was like being dragged under by language that refuses to let you breathe. Hubert Selby Jr.’s style is visceral, erratic, and unsparing—no quotation marks, no clean punctuation, no room to hide. The voices bleed into one another, mirroring the characters’ descent, and my Turkish had to mirror that chaos without becoming incoherent. The rhythm of obsession—whether it’s Sara’s television dreams or Harry’s junkie loops—had to pulse in every sentence. I leaned heavily on syntax to capture that collapsing momentum, often bending Turkish grammar to its limits while staying just this side of breakdown. This translation wasn’t just about rendering speech or thought—it was about capturing the psychic disintegration of people who can’t stop reaching for something that’s never coming.

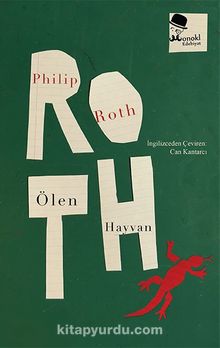

Philip Roth – The Dying Animal – 2011

Translating The Dying Animal was like being caught in a monologue that seduces and repulses at once. Roth’s language here is lean, obsessive, and unrelenting—a confession as much as a provocation. The hardest part was capturing David Kepesh’s voice in Turkish: articulate yet trembling with rage, lust, shame, and self-justification. Every sentence had to walk a tightrope between philosophical reflection and erotic compulsion. Turkish doesn’t offer the same tonal elasticity between high and low registers, so I had to carve space for shifts that felt natural but didn’t soften the edge. What made it especially intense was how close the voice gets to the reader—you’re not translating a novel, you’re translating a man’s mind unraveling in real time. It’s sparse, but it burns.

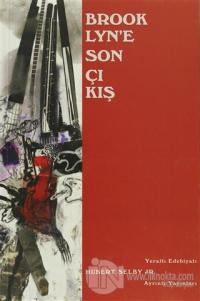

Hubert Selby Jr. – The Last Exit to Brooklyn – 2010

Translating Last Exit to Brooklyn was like stitching together a scream with no pause for breath. Selby’s prose doesn’t just describe marginal lives—it inhabits them with a brutal, unfiltered rhythm. The rawness of the language, the violence in the syntax, and the collapsing grammar all demanded that I let go of conventional Turkish flow. I had to find a register that felt equally feral, equally shamed and defiant. Each voice—Georgette’s longing, Tralala’s numbness, the mob’s cruel chorus—required its own emotional cadence, but all had to speak from the same ruptured world. There’s no safe distance in this book. The challenge wasn’t just technical—it was emotional stamina: staying inside a linguistic environment where every sentence feels like it could hurt you.

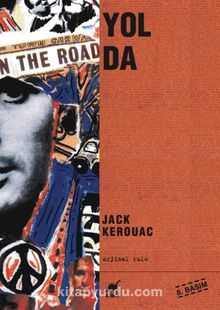

Jack Kerouac – On the Road: The Original Scroll – 2008

Translating On the Road: The Original Scroll was like chasing a thought that refuses to stop for breath. Kerouac’s spontaneous prose spills across the page in one long rush—no paragraph breaks, no censoring, no edits—just pure motion. Recreating that flow in Turkish meant breaking all the habits I’ve developed over years of careful translation. I had to let the language run, even when it felt like it was veering off the edge. The challenge wasn’t just rhythmic—it was tonal: keeping the ecstatic hunger, the longing, the speed, without falling into chaos or losing the pulse. The Original Scroll doesn’t just tell a story—it is the story, in how it moves, swerves, and refuses to stop. My job was to ride it in Turkish without taming it.

Tristan Hawkins – Isis – 2003

Translating Tristan Hawkins’ Pepper—my very first published translation—was where everything began. The book has a strange, brittle energy: detached yet intimate, emotionally fragmented yet stylistically precise. As a first-time translator, I was thrown into the deep end. There was no formula to lean on—just instinct, trial, and obsession. I remember trying to calibrate every sentence so it would carry the same tension in Turkish without tipping into melodrama or flatness. The voice was slippery: ironic one moment, devastating the next. I learned quickly that tone is everything—and that tone lives in the smallest choices. Pepper taught me how to be present in the text without overwhelming it, and how to build trust with an author’s voice line by line.